Joan DePaoli and Tony Bernhard

Excerpt from an unpublished manuscript

From Emptiness to Form and Back

An Introduction to the Art of the Dharma

Early Dharma Art

In the twenty five hundred years since the awakening of Shakyamuni Buddha, followers have been studying his teachings and practicing the path he prescribed in efforts at realizing the Buddha’s insight and putting an end to the suffering that seems to come along with the condition of being alive.

Any historical review of Buddhist philosophy and practice over the centuries will reveal substantial development and change.

As the Buddha’s teachings spread from the Buddha’s homeland in northeastern India, practitioners came to emphasize one feature or another of his teachings in accordance with the different cultural interests and predispositions of their parent civilizations. Today, as with the Burmese, Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetans, we are also seeing the heart of the Buddha’s teachings adapt to the cultural conditions in the west.

This book is designed as an orientation to this tradition and as a starting point for investigating the dharma through the gateway of artists who celebrate and explicate the Buddha’s teachings through their individual and cultural aesthetic expression.

For years after the death of the Buddha, no images in human form were made in deference to his request. He clearly stated that he was not a deity and feared that an image in his likeness might become subject to idol worship.

For several hundred years, footprints, dharma wheels, pillars and numerical references to the triple gem of the Buddha, the dharma—the teachings of the Buddha—and the sangha—the community of the Buddha’s followers, represented the Buddha’s teachings.

Lion Capital Pillar, King Ashoka reign, 3rd Century BCE, Vaishali, Bihar India

Later, when images of the Buddha came to be regarded primarily as reminders of the awakened being, the Buddha and his story were portrayed in the unique aesthetic style of individual cultures. Much as western Christian art adorning the walls of cathedrals in the west recounted the story of Jesus, narrative images and stylized iconography depicting the Buddha and interpreting his life and teachings appeared in the east.

Buddha, Teaching Mudra, 5th Century CE, based on earlier style of figurative Buddha, Ratnagiri, Maharasthra, India

Over the years, when reflecting on the Buddha’s insight and teachings, artists and craftsmen have been as articulate in translating the Buddha’s insight as have anyone engaging in conventional writing and commentary. Sculptors, painters and architects as well as gardeners, potters and such ritual leaders as tea masters have pointed to aspects of the dharma in ways unavailable to more conventional interpreters: displaying the demeanor of the Buddha in a transcendent mental state became the point of many commonly recognized renditions of the sitting Buddha

Artistic styles moved with artists and artisans who traveled along with adventurers and slowly migrating populations. Artistic styles mixed as teachings took root in new cultural soil and hybrid forms grew and transformed.

Representations of burial mounds, for example, were known as stupas were originally designed by architects in India to create a sacred space for devotees to practice the dharma by simple circumambulation of the mound.

On the tops of the earliest of these stupas, artisans were erecting ornamental finials that represented the Buddha’s enlightened mind in the same way, as did the bulging protuberance atop the heads of statues of the Buddha himself.

Stupa, 5th Century CE, based on early Stupa form, Ratnagiri, Maharasthra, India

Later, in Japan, this symbolism evolved into pagodas, which on their own stood for the presence of the enlightened mind.

Today, the interpenetration of contemporary cultures is bringing and mixing all dharma traditions in the west, and the commingling of artistic styles and traditions is mirroring the combination of teachings from the various traditions into new dharma formations.

The history of dharma art reflects the development of Buddhist thought and experience over the past twenty-five hundred years.

This book is designed as an orientation to this tradition and as a starting point for investigating the dharma through the gateway of artists who celebrate and explicate the Buddha’s teachings through their individual and cultural aesthetic expression.

Modern Dharma Art

The teachings of the Buddha began arriving in North America early in the 20th century. Increased contact with the rest of the world brought travelers and business people back to Europe and North America from Southeast Asia, China, and Japan bringing with them all forms of cultural artifacts, including artwork, architectural inspiration, and a philosophy of living which had a deep affect on dancers, musicians, artists and scholars.

Design esthetics from Japan first began appearing in the west in the form of teacups and other utensils used in Zen tea ceremonies. Asian sensibilities also began appearing in the architectural works of Frank Lloyd Wright, and Japanese woodblock prints had a strong influence on the Impressionist painters.

Increased commerce and cultural contact with the east increased the spread of the dharma in the west, clothed at first in artistic sensibilities that included painting, literature and music. Performance artists like composer John Cage, dance choreographers like Merce Cunningham and such popular groups as the Beatles were heavily influenced by the spirituality and esthetic understandings of the East. There were poets—Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Alan Ginsberg—visual artists such as Ad Reinhardt, Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell and Jasper Johns—scholars D. T. Suzuki and Robert Thurman. All these and more popular writers such as Alan Watts were translating the Buddha’s insight into the conventions of their own disciplines, the language of their own work.

Historically, cultural contact and interaction had occurred primarily through soldiers returning from war; in the second half of the 20th century significant contact came through the leaders in the peace movement who brought the dharma and related arts from Asia.

Visual artists were most attracted to the representation of ‘emptiness’ in the Zen ink paintings, and there was much experimentation and an expanded freedom in regard to subject matter. A statement by D. T. Suzuki became almost a mantra for many artists: one thing is no more important than any other as a means to enlightenment. This injunction was taken as permission to make any subject matter the focus of formal painting, and as a result, almost anything could—and did—become the subject of western art in the second half of the 20th century.

Few visual artists at first directly incorporated images of a Buddha sitting in meditation. Instead, artists wanted to present the dharma as directly as possible. And even more: the creation of artwork itself came to be regarded as dharma practice. Painter Phillip Guston said: “When you begin work in your studio everyone is there, your teachers, your friends, your parents. One by one as you work they all leave... when you’re lucky ‘you’ do.”

This is an image of the Buddha from Henri Matisse. It reflects the nature of the interest in the Buddha that was common at the beginning of the last century.

This vision of the Buddha is strikingly different from the older, classical images, the classical images that reflected the aesthetic of the different, earlier cultures.

Through reading lists, documented conversations as well as from letters and diaries, we can trace a developing interest in Asian culture as well as in Asian spiritual forms among western artists in the early 20th century.

As western impressionist painters increasingly came into contact with Asian art forms—specifically those from Japan, China and India—western artists who are not normally recognized as dharma artists were becoming increasingly immersed in eastern artistic, spiritual and cultural forms.

Along with learning about the artistic forms, these artists also became aware of the philosophical elements of the teachings of the Buddha. Van Gogh is especially known to have read and discussed ideas from Japanese Buddhist traditions.

Matisse’s painting visually illustrates how the dharma -- and the artistic content that come along with it -- takes on the cultural trappings of societies into which they migrate by displaying the effort of a western artist to visualize a Buddha from within the western artistic tradition.

This glass image combines reference to the Zen circle and a mandala. This combination of references from the Zen and Tibetan traditions was common among artists who used forms of the art alone or in combination to point to an insight. Most artists did not see boundaries in the traditions but all pointing to the same message, one dharma. The use of translucent glass as a medium suggests the possibility for insight.

A western-trained eye might not immediately notice the reference to the classical, calligraphic Zen circle or the broad silhouette of a Tibetan mandala, but American artist Chris Wilmarth intended both in this glass image.

In North America today dharma practitioners are finding themselves exposed to teachings from all three of the principle Buddhist traditions as they cultivate their meditation practices. Often, individual meditators incorporate and combine specific dharma practices from more than one tradition in their personal, individual practice.

Artists interested in the Dharma also have found themselves including references and even specific elements from all three different Buddhist traditions within a single work.

The use of translucent glass for this work also functions—like the use of mist in a Japanese landscape—to point to the empty void, the mind that shines through the arising and passing present phenomena.

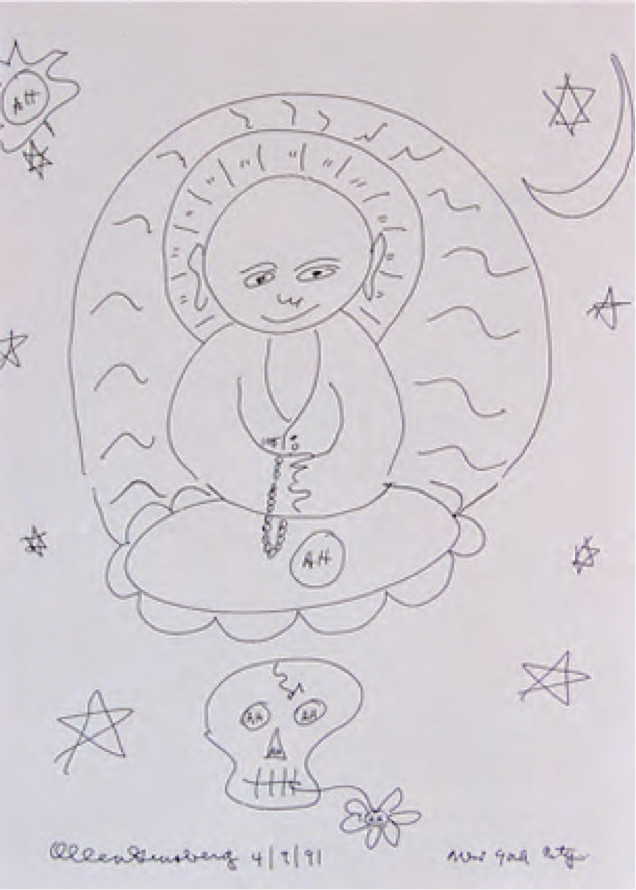

This drawing by Allen Ginsberg, Beat poet and dharma teacher of the mid-20th century, portrays the Buddha sitting on a lotus seat above a skull that is holding a flower in its mouth.

The overall image is reminiscent of the Tibetan paintings called thangkas, with the Buddha sitting on a lotus throne in the middle of the painting, surrounded by iconic images of all kinds, including skulls, flowers, stars, and so on.

Again, the general theme is interpreted in the visual language of the mid-20th century beat culture, an artistic milieu in which many artists were exploring various Buddhist and dharma philosophy.

Notably, this drawing is not an attempt to produce fine art in the sense that the term has meant in the past. It is not for the glorification of the artist, for the exploration of artistic style or for a display of artistic technique.

It is a simple, spontaneous depiction of an image of spiritual importance to the artist: much like a Zen calligraphic circle might have been.

Joan DePaoli

Joan DePaoli is an artist, art historian, author and lecturer, and is also a curator who, since 1970, has presented exhibitions of Buddhist art in both Thailand and the United States. Her researches include how visual art has been used both to commemorate the Dharma and to facilitate its practice since the time of the Buddha. She has a special interest in the Dharma's substantial influence in contemporary modern art.

Tony Bernhard

Tony Bernhard is an ordained Buddhist chaplain and teacher. He maintains an active practice with inmates in Folsom Prison and hosts sitting groups in Davis, California. He sits on the board of the Sati Center for Buddhist Studies and teaches regularly in the San Francisco and Monterey Bay areas and the Central Valley.